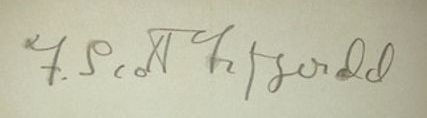

Born in 1896 in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald was a very conservative (in its original meaning), upright Victorian male who never lost his mid-Western view of life or his delicate sense of propriety, even when drunk. The reason why he could so ruthlessly chronicle the chaotic, destructive, careless, immoral Jazz Age (a term of his invention) was that he was so outside of it, even when he was in the middle of it. He was never able to bridge the gap between those two extremes; his writing was the gifted attempt to do so.

His drinking was punitive. It formed the self-destructive flaw within him, but he used his alcoholism to create exquisite, as well as mediocre, fiction. He saw quite clearly the reality of the people with whom he associated, which leads one to ask at times why he associated with them. The life of a writer, especially a writer who treats his life as primary source material for his stories, is not always lived to his advantage. F. Scott was as tormented by fame as he was thrilled by it: his dark night of the soul was nurtured through his inability to grow up fully before he grew old. There was a startling lack of self-reflection within much of his writing, although he could pen admirable and accurate advice to his treasured but estranged daughter.

Fitzgerald never developed into the maturity that would have permitted him the vision of a fully developed adult male who, in looking at himself, realizes the admirable reasons why he ought to be vastly different from the aesthetically handsome, almost beautiful youthful male who “won” Zelda through his swift success as a very young novelist. At that point in his life, the fix was in regarding his artistic soul and his creative self. Fitzgerald had been fiercely intent on becoming a self-reliant, self-made man. Exactly what he did with that self would become the basis of his self-loathing and his self-creating.

His later harsh judgments of the life he’d lived (of “whoring” his talent) bear witness to an astounding lack of foresight or even sight. He went through money like it was liquor while he went through liquor like it was money, living fast in the here and now. He wrote his early works in much the same manner. By the time that The Great Gatsby was written, F. Scott was a man yearning to be wise, but he was somehow never able to grasp hold of permanent wisdom. He was also a man looking toward demise. This novel would never earn him much money. His death ultimately proved the biggest lure for sales of his haunting, glittering masterpiece.

I’ve read “Gatsby” perhaps five or six times. Until the last time that I read it (summer 2012) I felt intimidated by the exquisite style; the sense-beyond-the-senses descriptions (hallucinations created, I believe, within the mind of Fitzgerald while he dried out, thereby producing the vicious and toxic cycle for his creativity); and by the compressed, controlled plot. This author worked with extreme diligence on editing, and it showed in “Gatsby.” During my last read of this novel, however, I did not feel intimidated by anything within it. I don’t know why. My guess is that I no longer strive to write like him in the craft of fiction. I have accepted my own muse and now see F. Scott as one of my highly esteemed teachers. Chapter VII was extremely long, much longer than any of the other chapters of the novel; but it’s a jam-packed chapter and the scenes all fit together as a unit, so sometimes there is the oddball chapter of expanse. Of course, the last two paragraphs of “Gatsby” are achingly beautiful. I disagree nonetheless with the philosophy contained within the final, sublime, immortal words (with their superb use of alliteration): “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” In essence, Fitzgerald was a poet. At heart, he was a romantic, but a pessimist. He always saw splendour inevitably linked with sadness and loss. He viewed life as a cycle of repetition, advancing somewhat, but inevitably drawn back into the past. This view was part and parcel of Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, as was his mid-Western upbringing which, much like Gatsby, was so out of place in the East. And here is where I miss the obvious: for all of my study and analysis of the text of “Gatsby” (it is a major template upon which I learned to write prose) -- I was not aware until my last reading of it THAT THE TITLE IS IRONIC. He wrote this masterpiece when he was not quite thirty, and it was pretty much all downhill for him from there, making the man even more tragic. “Gatsby” was published in 1924. His next novel was published ten years later, after a decade of creating personal debris that he then picked up, ragged piece by ragged piece, to rapidly re-formulate into fiction. Tender is The Night does contain beautiful passages, those soothing yet exhilarating signs of the quintessential Fitzgerald ability to craft a scene, and a setting, and to render into fiction the telling details of life that are simple, poetic, and powerful. The plot, however, is dismal, confused, even bleak; timeline and point of view are purposely blurred, but to no useful effect artistically.

My knowledge of French helped me enormously with his inclusion of this language in the text, but this reader worked far too hard to understand the plot. Reader was subjected to the painful, ghastly, wretched confessions of a tormented writer who, at this point in his life, believed that life was art and art was life. The wall between art and life had always been somewhat spongy and porous for Fitzgerald, but his descent into the advanced phases of alcoholism obliterated even that spongy wall. His personal life was coming completely apart and it bled completely into his writing. For some readers, Tender is The Night is a brilliant, pain-filled chronicle of the early disintegration of this literary genius. For me, each reading (there were several) was much like the booze that fueled it: a real downer. It serves as a stark contrast to The Great Gatsby in that “Gatsby” is an intricately woven, powerfully wrought work of fictional art in which Fitzgerald transcended his ego; Tender is the Night is a provocative display of at least one ego falling apart. Decades ago, I read The Last Tycoon. (In 1994 it was re-issued in an expanded version with discovered chapters that were “re-assembled.” The book was then re-named The Love of the Last Tycoon, but I’ve not read this version.) The experience was most frustrating. The fact that this novel was not finished by the writer because he died did not sway my opinion for or against it. I was willing to overlook the tragedy (“sudden” death) threatening to overtake the tragedy (unfinished novel).

As much as I admired the descriptive passages, those portions of solid writing stuck out like unsore thumbs amidst the patchy unevenness of the book. Alas, Fitzgerald without his editing skills was not Fitzgerald; Fitzgerald in Hollywood was not Fitzgerald. F. Scott Fitzgerald by this time was a broken man, blindly reaching for the stars, but they were the wrong stars. His fall, which was largely of his own making, from his pinnacle, which had been largely of his own making, was too redolent in each page. I was unable to finish even the unfinished book. A work associate observed me re-reading a page for perhaps the third time. He said, “Are you going to stare that page into submission?” I laughed and tucked that statement away in my mind. I believe that I used it in the essay, “The Blank Page.” It is mournfully sad that F. Scott never got beyond being a fierce critic and observer of the Jazz Age, but perhaps that role is what he was meant to fulfill -- he trapped himself early in his life with fame and fortune and he did not seem able to move past that phase of his young adulthood. And yet the man was unlike any other, writer or otherwise. He rushed at life; he did not wait for life to come to him. Filled with vibrant awareness, he dreamed without effort and believed far too much in these wondrous words that he wrote: “a sense of infinite possibilities.” He never saw the price for believing more in a possibility than in the reality that fed any possibility. He did not believe that a dream can cost a man, especially a dream that is not founded in reality. When I was nineteen and scrupulously studying the works of this writer, I was told by a Southern gentleman of the Tidewater region that I had to “take my ideals off their shelf and use them.” It was one of the best pieces of advice that I ever received in my youth. Someday it may form the beginning of a novel.

Fitzgerald was that charming combination of apparent contradictions that fascinates both men and women: fiercely competitive but also gentle; keenly intelligent but not intellectual or even academic -- literature was the only subject in which he excelled; finely sensitive but also bluntly, comically, and, at times, pointedly, even hurtfully, critical; gregarious but possessed of an intense “interior world” that cut him off from others; utterly honest as a writer but in total denial about the destruction of his own person. His life with Zelda was love and war and very little in between. The crumbling of two lives, one into alcohol-induced schizophrenia, the other into fatal alcoholism, was hardly a truce. In a very real sense, F. Scott Fitzgerald was both Nick Carraway, narrator; and James Gatz. His death on 21 December 1940 at the age of forty-four cut short a life that might have been. For this gifted idealistic man, the chance to be able to sense just one infinite moment of that one glorious possibility, to be granted just a grasp at seizing that opportunity -- this artist, Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald, in his romantic, doomed mind, would have been content, at least for a while.