I attended a Writer’s Conference in the early 1990s on the “up and coming plots” for the future, the ideas that a writer needed to focus on to sell. I felt slightly insulted but very infuriated by this “author” to whom I’d paid $90 for a bunch of bull and a mass of malarkey. His contention was that the readers of the future were persons of certain specific ethnicities.

“Target them. Write for them. They’re where the money of the future is.”

I raised my hand and this author permitted me my say, something that I ought to have warned him about in advance but, by that time, I was envisioning the clothes that would have been better paid for with my $90. In those days, $90 was a lot of money. (It still is.)

“I am not of those ethnicities,” I stated. “And I would not presume to write for anyone of those ethnicities. I am sure that people of those ethnicities can write for themselves of their own experience. It is my belief that the further away you get from your own experience, the worse your writing is.”

I might have added that poetic truth, or universal truth, is beyond the confines of any race, class, or “ethnicity,” but I knew that I was wasting my breath. The sizeable gathering took a short break after that commentary. I walked out of the Writer’s Workshop. It was my first, and last, of that sort of thing.

Plot is always linked to personal experience, no matter how much one tries to flee it. It does not mean, however, that one tells the story of one’s life. Far from it. Writing fiction is not re-creation; it’s creation, although invention is a more apt term. Good fiction is not the reproduction of life; it is the production of a construction of life in an artistic setting that has verisimilitude. On the other hand, very few elements in fiction are truly invented; the completely invented scene or setting is paltry and as thin as turnip soup.

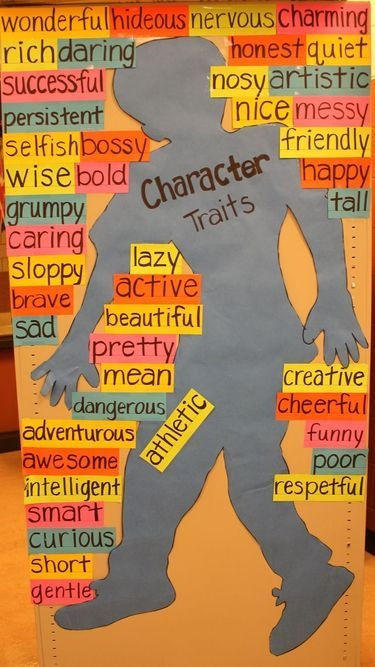

A physical character cannot be wholly invented; he or she must have some basis in reality. Any truly compelling or interesting character is a montage, a “construct” of features and traits from people known and unknown, seen and imagined. A totally invented character is simply unbelievable and awful, as is a “copy” of a person. Composites of character, setting, and scene make up fine fiction.

Elizabeth Bowen was an Irish novelist and short story writer. She also wrote very fine literary criticism. My decades-old photocopied pages of her Notes on Writing a Novel include the following:

“By the end of the novel, the character has, like the silkworm at work on the cocoon, spun itself out.” My note in the margin says, “And the writer too!”

Miss Bowen continues: “Completed action is marked by the exhaustion (from one point of view) of the character.” And the exhaustion of the writer! “Throughout the novel, each character is expending potentiality. This expense of potentiality must be felt.”

The reader must feel and understand that a character is making choices that exist among other choices, but the ones chosen are the logical, emotionally consistent, inevitable ones for this character. If that sensibility of the inevitable, or even the probable, is lacking, then the character is not believable, not real. The character is flat! Those words are perhaps the most appalling, wounding, and embarrassing for any writer to hear. “Your” character has not even reached the unenviable state of being which is, in the delightful words of Dear Daughter, “Fizzed out.”

The plot is a destiny that the writer must accept, or he will fail his art, the poetic truth which is the vision within him that compels him to write. Miss Bowen more than aptly sums it up:

“Plot might seem to be a matter of choice. It is not. The particular plot for the particular novel is something the novelist is driven to. It is what is left after the whittling away of alternatives. The novelist is confronted, at a moment (or what appears to be the moment: actually its extension may be indefinite) by the impossibility of saying what is to be said in any other way.

He is forced towards his plot. By what? By ‘what is to be said’. What is ‘what is to be said’? A mass of subjective matter that has accumulated – impressions received, feelings about experience, distorted results of ordinary observation, and something else – x. This matter is extra matter. It is superfluous to the non-writing life of the writer. It is luggage left in the hall between two journeys, as opposed to the perpetual furniture of rooms. It is destined to be elsewhere. It cannot move till its destination is known. Plot is the knowing of destination.”

My very dear friend is invaluable to me as a “reader” because she so superbly guides me (perhaps without even knowing it) toward the “knowing of destination” that must be the plot of any novel. She asks why a certain child character would not be older, or, more importantly, act older. She questions whether a female character ought to be more aware of something, or if a certain scenario is believable enough. She challenges particular details of my plot and characters in terms of verisimilitude. I must then defend my decisions about those aspects of the novel in progress. I sometimes change my mind completely about something or I might just “tweak” the character or a setting.

My “reader” requests that I think those precise elements through -- and then define for her precisely “what has to be” versus “what might be” in my novel. The worst-case scenario - What I’d Like It to Be -- must be avoided at all costs!

During the many years that I “waited” to write my novels, I was, as Dear Daughter says, “collecting images.” She states that’s what I go about doing, collecting images. Quite without knowing it, I might add. This collecting of images is the accumulation of subjective matter that Miss Bowen mentions. That visual process is the reason why when I look at something, I see things that other people do not see.

It is also the reason why I often fail to see very obvious things that other people automatically see. I am focused on analyzing and synthesizing experience for the purpose of “later” fiction. This sizable difference between my focus and the focus of others is usually viewed as a dumb blonde moment.

This “later” fiction arrives when I, the “objective” writer, know where the subjective matter is going. But until that awareness of “destination” arrives within me, I have no idea where that subjective matter belongs or where it “is going.” I only know that I’ll use it for something someday! I’ve got quite a data bank in my head of what most people would consider superfluous, trivial information.

I am rarely aware of this “processing of reality” (“the distorted results of ordinary observation,” as Miss Bowen puts it). There have been many times in my life, since childhood, when I have experienced an event “happening” as “a scene,” simply because it feels like one: the structure is there; the setting; and other necessary components that quite literally “play out” before my eyes.

Such an experience has, at times, been frightening because although I sense that I am undergoing vastly different visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory textures from those of “unrecorded” life, I do not know why it is that way. My senses are too imbued with this extremely heightened processing of realty. It is only later, usually much later that I realize that my mind has “recorded” elements of a scene with an extraordinarily intense awareness of detailed sensual “information.” That information later becomes distorted when I use it for the purpose of plot.

“You are by your very being a writer,” my very dear friend once told me.

I agree. Countless times I’ve tried to escape the demands of this literary gift by painting or singing or drawing, only to face the fact that those other talents function in the service of my writing.

My life is my life, however, and my art is quite another thing. The storage of experience that I work from might be compared to a vast supply of clay for a sculptor or many different tubes of paint for the painter. It is necessary for me to have a powerful grasp of reality before I perchance depart reality to create “reality” in the world of fiction. My powers of concentration and intense focus upon the world around me are used to produce the realness that goes into my fiction.

Yes, there are times when I prefer my world of fiction to the “real world” because the “constructed” world makes more sense. I do not, however, use that world as a means of escape or a hiding place. To quote W. Somerset Maugham,

“Reverie is the groundwork of creative imagination; it is the privilege of the artist that with him it is not as with other men an escape from reality, but the means by which he accedes to it. His reverie is purposeful.”

And so my reverie helps to reinforce my fundamentally sound grounding in reality. Reality nonetheless always intrudes upon “reality,” and I then must return to it routinely, often unexpectedly.

No matter how involved I may be in a flight of fancy within a foreign land of fiction, the pork chops and chopped potatoes have to be seasoned and put into the oven; the cell phone plays its ring tone; the UPS man delivers a reward for all of my hard work; a pile of unfolded, clean laundry stares at me from a leather arm chair and, out of conscience, I fold the items. As I fold, I ponder some elements from the scene in progress.

From out of nowhere, a bobcat or wild, abandoned tabby cat emerges on the trail that I view from my sunroom: I must protect my domestic animals. Even Annabella, the muscular black Burmese cat with the huge claws and the baseball bat of a tail, cannot fend off wild animals, and she knows it. She hides. Gabrielle, the pitifully neurotic, thin, softly beautiful Snowshoe, with her Q-tip paws and tiny pale pink claws -- this small feline crouches in wait to attack whatever threatens her food bowl. Annabella remains in hiding; she knows that I’ll chase away the bobcat or “Thing Cat,” secure the perimeter, and then refill the food bowls.

The trap for yet another varmint cat will be set out again that night. We will inevitably catch a rather large, angry raccoon or big, docile possum. The possum loves salmon, by the way.

Just as I begin some revisions, my 13-inch-beagle will insistently sound the signal that she needs to go outside. I let her out, and then, the minute that I sit back down, Bridget sounds an even more insistent alarm that she needs to come back in -- as if I threw her out the door!

One does not ignore Bridget, the alpha female. I must spring into action in my life, and then return to the action of my plot. And yet these interruptions or breaks from the weaving of images into a plot often serve to awaken within me other images, symbols, words, and memories that further serve or, indeed, enhance the “realities” of my plot.

Miss Bowen further explains the “realities” of plot:

“Plot is diction. Action of language, language of action.

Plot is story. It is also ‘a story’ in the nursery sense – lie. The novel lies, in saying that something happened that did not. It must, therefore, contain uncontradictable truth, to warrant the original lie.”

If one were to simply write a story of the events that occurred within an hour or two or even three of one’s life, believing that such a chronological tale of occurrences would create dynamic action and thrilling interest; the reader would be bored to the point of doing what I always recommend to a boring tale: throw it away! If, however, one takes only the events within any given time frame that can be used, molded, adjusted, expanded, altered, and re-viewed to fit the plot – and write of them in a compelling, original, and evocative way – then the reader would be intrigued. I recommend: Keep reading!

I learned the following statement to be true from experience, but it is worth quoting from the wise Miss Bowen: “Remote memories, already distorted by the imagination, are most useful for the purposes of scene. Unfamiliar or once-seen places yield more than do familiar often-seen places.”

During her review of the draft of what was then called “Nottingham,” Reader, a well-traveled woman, asked me, “How many times have you been to Paris?”

“Never.”

“And Provence?”

“Never.”

She was shocked. “You write just like you‘ve been there! How about England? You must have been to England. You describe it so well!!”

“Not England either.”

Reader was amazed at my powers of description.

I was recently asked by my hairdresser if I visit the place that I am going to write about -- to research it. I quietly said, “No.” And then I explained that the writing is more powerful if I use my imagination rather than rely upon visual descriptions obtained purely for the purpose of writing.

To jot down specific details, I have traveled to public places, such as the California State Capitol and various buildings in downtown Truckee, including the Amtrak station. That “field work” allowed me to draw a picture in my mind of a setting that must be precise. Those locales, however, are not venues of the past or reservoirs of memories and emotions. And I voraciously read coffee table books of foreign lands, villages, and places where I journey in my imagination. Often I’ve read such books just for pleasure, only to find that many of those pages provided settings and ideas for fiction.

As for actual locations, regions, and locales, after a certain point in my life I decided not to return to “places of my past.” I sensed my need to create, or assemble scenes, from those memories. For the novelist, the memories of a place, with its unique, cherished grains of vision -- that secret cache contains the stuff that fiction is made of. That raw material must not be disturbed within the memory of the writer by updating it into reality, into the here-and-now. The sight of the (usually horrid) renovation or remodeling of a home (or rapid expansion and “modernization” of a town) from long-ago would be horrifically destructive for me on an artistic as well as personal level.

I’ve created winter scenes when it was 100 degrees outside; and I’ve described the heat of Provence while sitting by a roaring fire in the fireplace during the damp cold fog of winter. The “reality” of the scene being constructed supersedes real weather.

Some final words of advice from Miss Bowen about plot:

“Plot must further the novel towards its object. What object? The non-poetic statement of a poetic truth. Have not all poetic truths been already stated? The essence of a poetic truth is that no statement of it can be final.”

I would gladly have paid $90 to have heard those words, or even a fraction of them, spoken at that Writer’s Conference.